|

|

|

|

|

April 2, 2004

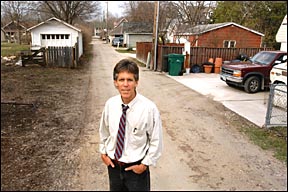

Mr. Martin's neighborhoodby Teddi BarronMichael Martin found his academic calling in the alley. For the past decade, the associate professor of landscape architecture has explored the social and cultural nooks and crannies of residential alleys. Familiar to residents of Ames' Old Town District, where he regularly walks the alleys with students in tow, Martin is one of only a few academics nationwide that researches neighborhood landscapes. He wants to under-stand how the physical design of the landscape relates to the quality of social life of neighborhoods. The lessons learned can help inform contemporary neighborhood design. "I think old neighborhoods really were designed at a time when we weren't quite so mobile. They supported an interactive social structure that modern suburbia doesn't. I'd like to return to the old form and build on it," he said. Martin has looked closely at the evolution of alleys. He has documented their change from residential service lanes to culturally expressive spaces and places for neighborhood social interactions. "Alleys are expressive, revealing and messy. They inevitably reveal much about the lives of current and past inhabitants. But they also have a social dimension," Martin said. "Alleys are an alternative network, like a connective tissue in the neighborhood. They are a safe, shared landscape that allows social connections to occur," he said. The notion that alleys are social space has sent Martin down a new path through the neighborhood landscape. "My original interest in alleys has grown into an interest in any type of neighborhood space that was effectively designed to be useful socially," he said. Now, Martin is examining 20th century experimental communities that successfully used landscape design to foster social interaction. One community is Radburn, built in New Jersey in 1928. The planned community, which was designed to keep cars away from pedestrians, focused on the landscape, not the street. "Instead of facing the street, the houses faced a park, which was meant to be the community social space. However, the lane and parking court at each house became the social spaces. Kids played in the lanes and people hung out there. Essentially the lanes were alleys," Martin said. Although Radburn didn't catch on as a suburban planning model, a developer replicated the plan in a Winnipeg woods 20 years later. "Like Radburn, Wildwood Park in Winnipeg has a remarkable cohesion and sense of place. People don't want to move. If someone wants a bigger house, they will replace the existing house with a new one, rather than move. The neighborhood actually has reunions every year," Martin said. Martin's interest in the neighborhood as a social space goes all the way back to when he was a kid playing in the street in his Atlanta subdivision. "Our street was a cul-de-sac. It wasn't designed to be a social space, but that's what it was. I was always intrigued by how people adapted that neighborhood -- there were certain 'hotspots' where all the kids gathered or the neighborhood celebrations took place," he said. Martin went on to study landscape architecture at the University of Georgia and joined an established Atlanta landscape architecture firm. "We worked with a very suburban aesthetic and were good at designing with the hills and trees of north Georgia. But we weren't aware of the social factors in design. We didn't innovate or question the status quo. That was frustrating to me. After a while, I started to believe that more was possible." He left his successful practice after 10 years to attend graduate school at the University of Oregon. "I wanted to learn historical examples of neighbor-hood landscape design that could effectively inform contemporary design," he said. While doing case studies in graduate school, he spent time in many neighborhoods, gaining an understanding of the way people interact in a neighborhood. "If they had a place that was important to everyone, like a back alley, it gave the neighborhood a sense of cohesiveness. There were a lot of socially healthy things about that -- people were connected to others in the neighbor-hood and it was great boon to people with kids," he said. "It's possible for these things to happen, either by accident or by design. It's also possible to design neighborhoods where it almost can't happen," he said. Most residential developments since World War II used a street pattern based on cul-de-sacs, loops and other forms that don't have cross connections, he said. "It's popular for a lot of reasons, but it's also pretty insular -- most streets dead end. Unlike streets in a grid pattern, they aren't connected or used much by people who don't live on them." A more recent trend that accounts for about 10 percent of residential development is "new urbanism." A design movement that responds to the car-centered, suburban sprawl of the past 50 years, new urbanism promotes development based on the traditional 19th century town plan. Neighborhoods are diverse, walkable, visually integrated, mixed-use communities. The original design of Ames' Somerset development was new urbanist. Although new urbanism de-emphasizes cars by eliminating driveways and locating garages on alleys, the design is still street-oriented, Martin said. "New urbanists believe in the street as the community space. That's why houses have front porches and are the exact same distance from the sidewalk. But what about the backside, the part of the neighborhood that's more protected? There's a great value for kids to have another side that can provide protection and be available as a social interface," he said. "New urbanism is a very important trend. It's more than nostalgia. But new urbanism isn't grounded very well in behavioral study. How do people really use places? How is the landscape supportive of children or not? Those kinds of questions don't normally enter into the literature you read on new urbanism," he said. Martin would like new urbanists to learn from places like Wildwood Park and Radburn. "What will the next form of Radburn look like? How would you create a design program and conceptualize about the design of the neighborhood, knowing what we know about the social virtues of Radburn and the aesthetic virtues of new urbanism? "I'd like to bring those two approaches together to develop a hybrid model that landscape practitioners can use." |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2004, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |