|

|

|

|

|

March 12, 2004Global warming at the local level

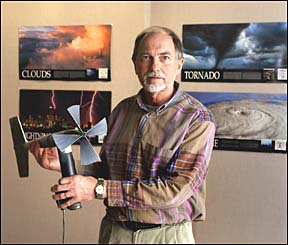

Agriculture Communications The forecast for 2040: More snow. More rain. More droughts. More extremes. This winter may have been a harbinger -- Iowans shoveled through near-record snowfalls, the fourth largest in 100 years. Gene Takle, professor of agronomy and geological and atmospheric sciences, believes such extremes may be the norm in the future due to global warming. "It's clear that the planet is warming and it's warming at an unprecedented rate," Takle said. "Something as big as this planet changes very slowly, so when we see changes that are large and abrupt, in comparison to a normal scale of change, it's alarming." During the last two decades, an increase in global temperatures has caught Takle's attention. Scientists predict that a doubling of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere could increase the mean global temperature from 3 to 10 degrees over the next century. Such temperature increases could bring about extreme weather. Takle compares it to placing a pan of water on the stove to boil. "We've cranked up the heat, so things will happen faster and more intensely," Takle said. "More precipitation and more heavy rainfall events mean more chances for flooding. There also may be more droughts and longer intervals between rain events. There may be two weeks between rains instead of one week and that's pretty significant for agriculture." In a study to be published this spring in the Journal of Geophysical Research, Takle and three other Iowa State researchers looked at how global warming would change weather and hydrology patterns in Iowa and the rest of the upper Mississippi River basin, which includes portions of Minnesota, Missouri, Illinois and Wisconsin. "We used a climate model that would show the impact of global change on a regional level," Takle said. The modeling is similar to the concept used to forecast the weather for the six o'clock news. While those forecasts predict temperature highs and lows for a five-day period, Takle's climate model provides a broader forecast for the future. To test the climate models, scientists input historic data from past weather events and compare the results to the actual event. When the regional climate model was combined with a soil and water assessment model (a tool that measures land-use impact on hydrology), the results for the upper Mississippi region indicated an 18 percent increase in snowfall, a 51 percent increase in surface water runoff and a 43 percent increase in groundwater by 2040. The changes would increase water runoff into the Mississippi River by 50 percent. "That's pretty major," Takle said. "The most significant outcome of this model is that it projects a 21 percent increase in rainfall. That translates into a 50 percent increase in stream flow." Takle is confident there will be increases in precipitation, but he said it's difficult to predict how it will be distributed. Rainfall totals for any given year may be the same, but the rain may be dumped in shorter, more severe storms, which could result in flooding and erosion. Besides the impacts on agriculture and water resources, climate change could influence other segments of the basin, such as insect populations. Takle said regional climate modeling helps scientists predict possible climate changes. "Policymakers use economic models and demographic models to project how cities are going to grow and future needs," Takle said. "Why shouldn't we do the same with the climate?" The sobering fact is that even if Americans quit driving and turned off the power plants today, the global temperature would continue to increase for another 50 years. Takle said excess carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. Scientists have been considering the effects of scenarios that include a doubling of greenhouse gasses; now they are considering the results if greenhouse gasses triple. "The reality is that we can't plant enough trees to take care of the amount of carbon dioxide we emit," Takle said. He said he isn't a street-corner preacher on the topic. But if someone asks, he'll present his views because he's passionate about what is happening. "I'm trying to raise the consciousness of the public. I talk to church groups, Lion's clubs, the Kiwanis, school groups and utility companies," Takle said. "We need to get a dialogue going between climatologists and decision-makers. They need to understand this problem and start asking probing questions." |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2004, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |