|

|

|

|

|

January 30, 2004Disability resources serves more than 700 students

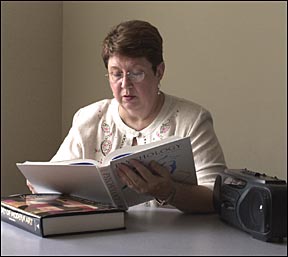

One former student has landed his dream job in California. Another is a year away from a degree in dentistry. Both recently contacted Iowa State's Todd Herriott to tell him how they are doing. They wanted him to know how much they appreciated disability resources (DR), the program Herriott coordinates. All DR participants are self-identified. A DR staff member reviews medical records and conducts an interview to determine a student's eligibility for services. Herriott said one of his biggest challenges is that students resist DR services out of pride and a desire to be independent. He said he suspects that some first-year students come to his office at their parents' urging but do not return even though they are eligible for services. Of that group, about 65 percent eventually return to the office. And they improve their performance by more than a full letter grade, Herriott said. "We respect pride and independence. Our accommodations depend on students' taking control and working hard, and we want to be as invisible as possible," Herriott said. Students turn to DR for support in dealing with such things as sensory impairments (vision and hearing, for example) or impairments affecting mobility. Approximately 65 percent of students served by DR are affected by learning disorders (of written expression or word decoding, for example), attention deficit disorder (ADD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Herriott said students with ADD or ADHD face difficult tradeoffs in using drug therapy. Some medications can help improve concentration for part of a day but also can cause sleeplessness. Class schedules, job schedules and study schedules affect timing of medications in what Herriott described as a "constant state of bargaining." DR staff members can help students develop schedules that take their disabilities into account. Studying for no longer than an hour at a time, with breaks for physical activity, works for some students. Students who listen to books or lectures on tape need to adjust for the fact that listening to the spoken word takes 2.5 times longer than it takes a typical reader to cover the same material. "Many of our students have been told they are not doing their best. Sometimes we help them come to terms with two things -- they need to work a lot harder than other students and they need to work in different ways," Herriott said. Technology helps. Some students combine note taking with recordings made on tape recorders with counters. If they realize they have lost concentration, they note the number on the tape recorder and go back to that section to review the original lecture. The DR office provides the tape recorders. The office also can provide such things as computers and software, and books on tapes or CDs. And DR arranges for desks and lab tables that accommodate wheelchairs. Herriott said he sees evidence that personal digital assistants (PDAs) are good tools for some of his students, though his office cannot provide them. "They are mainstream technology, which our students want. And they can be used for many functions, including some that are purely social and entertaining. The more useful they are, the less likely it is that they will lose them or leave them behind. They have a lot of advantages over paper calendars and multiple notes and reminders," Herriott said. Compared with other ISU students, DR participants have slightly above-average GPAs. Herriott noted that faculty cooperation is an important ingredient of success. Some standard ways of measuring academic achievement may not measure the achievement of a student with a disability, he said. "We have faculty members who are wonderful allies of students with disabilities and we have some who still resist the idea that DR is an essential part of equal access to education. The university's support for DR is clear, though," Herriott said. The budget for DR comes from the university's general fund. The most expensive DR service is sign-language interpretation, which can cost between $15,000 and $20,000 per semester. Iowa's vocational rehabilitation program may pay half of this amount and departments and colleges can be billed for a small portion, a maximum of $50 for departments and $200 for colleges per semester per student. DR personnel include six full-time staff members, two graduate assistants and part-time students. Note taking in class is one student job. The student employee keeps one copy; the other copy goes to a fellow class member with a disability. Staff members act as advisers, one-on-one trainers, mediators and group coaches. Students who are experienced in using DR services serve as mentors to incoming students. Herriott said his staff is involved in general support, training and advocacy. One payoff comes in phone calls and notes from former students. The student who landed the dream job in California described the interview process, which included proud and frank talk about the resourcefulness and determination involved in overcoming a disability. "We support them, but their hard work is the key," Herriott said. |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2004, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |