|

|

|

|

|

January 30, 2004The right chemistry

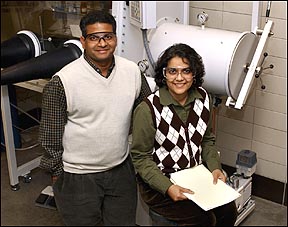

Balaji Narasimhan is a movie buff -- his DVD collection tops 1,300. He currently is writing a screenplay that one day he hopes to see developed into a feature-length film. Nonetheless, his "day job" as a biomedical polymers, or plastics, researcher in the College of Engineering was inspired not by the "Mrs. Robinson" flick, but by a lifelong love of science and parents who enveloped him with encouragement and support. Likewise, Surya Mallapragada, who found her refuge as a young girl in books rather than films, nurtured her love for science through the chemistry kits her father bought for her throughout her childhood. In time she, too, began thinking about plastics. An associate chemical engineering professor like her husband, today Mallapragada leads research teams who investigate how the biodegradable forms of these materials can force nerves to regenerate. Together, Narasimhan and Mallapragada, colleagues and husband and wife since 2000, are emerging as major players in biomedical research. Narasimhan designs biomaterials, such as biodegradable plastics, to deliver drugs more efficiently to specific parts of the body. He and his team study how polymer capsules could release vaccines over an extended period of time, eliminating the need for booster shots for diseases such as tetanus or diphtheria. The antigens would be injected into the body encased in tiny spheres, one-millionth of a meter in diameter. The size and chemistry of these spheres would control when and how much antigen is released into the bloodstream. Though these materials have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other applications, they have not been approved for transporting the vaccine, and they have not been tested on humans for this purpose. Mallapragada's research investigates how these polymers can be used in tissue engineering, or promoting growth in damaged tissues. Much of her work has focused on nerve regeneration, using polymers that guide the repairing nerves to grow in a certain direction. Though her studies primarily have dealt with rebuilding nerves in arms and legs, Mallapragada also now pursues these applications on optic nerves. Her polymer research extends to gene therapy as well. In these studies, Mallapragada examines how to deliver "suicide genes" to cancer cells to destroy them, using polymers that are pH and temperature sensitive to deliver the genes. Like her husband's, Mallapragada's research is not ready for human testing. Side by side The couples' personal lives, as well as their careers, have paralleled almost eerily. The India natives attended the academically elite Indian Institute of Technology as undergraduates, earning bachelors' degrees just a year apart. Both pursued Ph.D.s in chemical engineering at Purdue University, where they became acquainted. Each then chose the professorial life, Narasimhan joining the faculty of Rutgers University and Mallapragada hired as an assistant professor at Iowa State. Their decision to marry led to Narasimhan's relocation to the Iowa State faculty. Three years later, the tenured duo is emerging nationally onto the science and medical stages. Within the past year, both have been named among the "Top 100 Young Innovators" by MIT's Technology Review magazine, the first husband and wife team to earn the honor. They've snagged early career achievement awards from the likes of the National Science Foundation, 3M and the Whitaker Foundation. Their research is funded by such prestigious entities as the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Energy. Google their specialties and their names appear with increased frequency. And they're barely 30. So what is it like to be a young, successful, respected power couple in academe? You'll have to ask someone else because neither Mallapragada nor Narasimhan has an answer. They talked recently in Mallapragada's Sweeney Hall office about their work at Iowa State. Quick to smile and unfailingly polite, the couple nonetheless has little interest in exploring "star" status within academe. Ask them about their specific research projects and they're eager to share. Compliment them on their many accolades and they will acknowledge them, but with humility. "Professional recognitions do give you a better standing in your field," Mallapragada said. "They usually help raise your stature -- but I've never felt any of the pressures that sometimes go with all that." Down the road Indeed, both scientists are quick to divert the reporter to more comfortable topics -- the supportive environment they've found in the department of chemical engineering, how grateful they are to graduate students who are both creative and hard-working, how the presence of the College of Veterinary Medicine and the Ames Laboratory enhances their research opportunities. "When we were trying to decide which one of us would move so we could get married," Narasimhan recalled, "I thought Surya was kidding me when she kept talking about how great everything was at Iowa State. And while it was a big challenge when I moved here, having to re-establish myself professionally when collaborators at Rutgers already knew my research and my energy, I have absolutely no regrets. I'd do it all over again." Even so, everyone knows academe is a competitive jungle, right? What happens when awards come to one and not the other? When only one comes home with the top research grant? And can you ever get away from work? "I wouldn't have this any other way," Mallapragada said. "I learn a lot from Balaji. When I come up with ideas at home for my research, I can have immediate discussions about it with a colleague. We have a very understanding relationship, a very supportive one. We recognize each other's strengths." So what do two notable scientists really want as they edge ever closer to the top of their game? "Much of this type of research is still hit and miss, very much a shot in the dark," Narasimhan explained. "I want it to be more rational. Down the road, I'd like to be known for my creativity in this field, and for affecting the way people are able to live their lives." "I'd certainly like to be considered at the top of my field by the time I retire," Mallapragada added. "I'd like to know that I made a difference in this field, and that my work opened some new avenues for others." |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2004, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |