|

|

|

|

|

|

March 17, 2003 Midwest Forensics Research Center Glamourless work in pursuit of the truth

They met in an airport, two men amidst thousands hustling through the terminal that day. One man was looking for answers; the other believed he held them. Eventually, they met again, this time in an FBI cafeteria. At last, one convinced the other he had "the goods." In short order, a team of FBI forensics experts was pounding the hallways of the Ames Laboratory Nope, this isn't the latest installment of the glitzy twice-weekly CSI television series. It is, in fact, the story (albeit a bit dramatized) of how Iowa State University was "discovered" as one of the nation's premier hotbeds for forensics research. Ames Laboratory Director Tom Barton heard back in 1997 that the Federal Bureau of Investigation was searching for new forensic science and scientific protocols. Barton also knew that across the ISU campus, researchers were conducting countless investigations that ultimately could aid in forensics work. True story: Barton did meet an FBI deputy director in both an airport and the FBI cafeteria to pitch the university's work, and indeed, those conversations led to a campus visit by FBI agents. FBI-ready What they found was a group of scientists teeming with research projects and ideas that benefit forensic science. Forensics refers to any aspect of science that relates to the law, or the use of technology to analyze evidence from crime scenes. This could include personal identification study (think fingerprints or DNA analysis), firearms IDs (recapturing serial numbers), psychiatric profiling, document examination (tracking forgeries or counterfeit operations, for instance), computer animation (recreating crime scenes or vehicle crashes) or statistical analysis (assessing probabilities). In time, the FBI, along with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), granted funds to five forensics research projects on campus. They included:

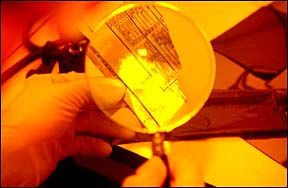

Enter state criminalists By 1999, groups of Ames Laboratory and IPRT scientists were meeting with Iowa Department of Criminal Investigation examiners and criminalists to assess mutual interests. Scientists Robert Lipert and Ruth Shinar spent a week in the DCI crime lab learning its investigative protocols. Soon after, two forensic technology development projects were proposed and ultimately funded by IPRT. These were carried out by Microanalytical Instrumentation Center researchers and support engineers in the Ames Laboratory's Engineering Services Group. Both projects aid in fingerprint identification. The first, a "glove box" designed by Lipert and constructed by Terrance Herrman, allows the easy introduction of evidence into its chamber, close observation of the fingerprint development process and control of both temperature and humidity. Liquid superglue is vaporized and distributed within the box's walls; superglue fumes are attracted to fingerprint materials, adhere to their ridges and valleys and form a lightly-colored polymer that examiners can then inspect under natural or other light sources. The DCI has been using the glove box for nearly a year, and its fingerprint examiners report they now develop 200 to 300 percent more fingerprints than they were using more conventional methods. The second project was a vacuum chamber designed to develop more specialized fingerprints. "There are difficult problems associated with developing and stabilizing fingerprints on plastic surfaces," Ames Laboratory's Todd Zdorkowski explained, "and this is the kind of evidence often found in clandestine labs or drug abuse sites." Once considered too fragile for development and identification, those types of prints now can be stabilized by a novel chemical process developed by ISU student intern Elizabeth Nelson. Made from Ames Lab surplus piping, the vacuum chamber is large enough to hold a rifle, and has also been turned over to the DCI for use. Forensics center is joint effort As these and other productive relationships continued to thrive among ISU researchers and the DCI staff, examiners and criminalists began referring university scientists to their colleagues in surrounding states. The idea of a Midwest Forensics Resource Center was born in 2000, with the Ames Laboratory and ISU as its administrators. Initially, IPRT provided seed money to fund the center's pilot-phase projects. By 2002, however, its successes were evident enough that Congress approved $3 million for the center, with the National Institute of Justice overseeing the funding. Just last month, the center received word that Congress has approved an additional $3 million award. These dollars will continue to fund projects that carry out the center's four main missions:

In another case, two Iowa men died under unknown circumstances while sleeping in a tent, and family members of one of the men suspected foul play. In particular, they believed someone might have damaged the space heater in the tent to electrocute both men. An electrical safety specialist in the Ames Laboratory's Engineering Services Group examined the heater and concluded there was no obvious evidence to suggest tampering. To better meet these distinctive casework needs, the MFRC hopes to establish a database corralling all the region's special resources so individual crime laboratories will have better access to the local expertise that exists in colleges, universities and specialized laboratories in the region, Zdorkowsi said. So even with these shortages, is it safe to say these specialists don't depend on CSI for guidance and inspiration? Shaking his head ruefully, Zdorkowski said, "CSI presents a very distorted and romanticized version of work in a crime lab. The work is not glamorous; the backlogs are huge and always growing. Most analytical procedures are well established and must be done with a high degree of analytical precision and careful attention to every detail associated with handling the evidence -- and performed on deadline. "Every examiner's work must be inspected and corroborated by another examiner before it can be released, and some examiners also find their work challenged in public," he continued, "either by aggressive attorneys or in the press. The pay is modest, facilities tend to be crowded and the stress levels are high. "But the one characteristic that seems to be common among all criminalists and examiners I know, and the one thing that seems to bring them to work each day, is their absolute love of the truth. Defense attorneys advocate for the suspect and prosecutors advocate for the victim, but examiners advocate for the truth." ISU departments and their scientists currently conducting research pertinent to forensic science include: Agronomy: Michael Thompson Ames Laboratory: David Baldwin and John McClelland Animal Science: Susan Lamont and Max Rothschild Biochemistry, Biophysics and Molecular Biology: Marit Nilsen-Hamilton Botany: Lynn Clark and Harry Horner Chemistry: Daniel Armstrong, Samuel Houk, Klaus Schmidt-Rohr, Patricia Thiel and Edward Yeung Electrical and Computer Engineering: Douglas Jacobson Entomology: Joel Coats Food Science and Human Nutrition: Patricia Murphy Materials Science and Engineering: Scott Chumbley and Bruce Thompson Mechanical Engineering: John McClelland Psychology: Gary Wells Statistics: Alicia Carriquiry Zoology and Genetics: Fred Janzen |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2003, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |