Inside Iowa State

Inside ArchivesSubmit newsSend news for Inside to inside@iastate.edu, or call (515) 294-7065. See publication dates, deadlines. About InsideInside Iowa State, a newspaper for faculty and staff, is published by the Office of University Relations. |

March 31, 2006 Fishing for answers to cancerby Samantha Beres A small room in the basement of Molecular Biology smells slightly of fish. It should. Thirty shoebox-sized fish tanks housing hundreds of zebrafish are stacked in racks along one wall. For Jeffrey Essner, a new faculty member in genetics, development and cell biology, it's a temporary space. This summer, he'll set up a zebrafish facility in Science II, where rack after rack will hold 1,000 of the plastic fish tanks and many thousands of fish.

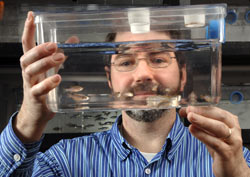

Jeffrey Essner's work with zebrafish is intended to lead to new treatments for cancer. Photo by Bob Elbert. The zebrafish facility will introduce a new model system to Iowa State for researchers who are studying vertebrate development. And Essner will continue his research: looking for genes in the zebrafish that will lead to new treatments for cancer. Why the zebrafish?Some might even ask, why fish? But the use of fish in research is not new. In 1910, President William Taft asked Congress to fund research laboratories that would study cancer in fish. Impetus for the request came from a scientist who was studying thyroid cancer in trout. The zebrafish was an early model system, but didn't become popular until the mid 1990s. Zebrafish as far as model systems go are low maintenance. They don't take up much space. Adults grow to about an inch and a 3-litre tank can hold up to 60 of them. They also develop quickly. Twenty-four hours into development, there is a beating heart. Yet another advantage Essner points out is that the embryos develop outside the mother. "The wonderful thing about these fish is that they give these optically clear embryos and so you can simply look at these embryos and see what's going on inside of them under a microscope," he said. Though these tiny fish might seem a far cry from us humans, many genes in the zebrafish have the same function as their human counterparts. Essner's workEssner is working to find genes in the zebrafish related to angiogenesis, the development of new blood vessels. A healthy body maintains a balance of angiogenesis, but disease occurs if too many form. For instance, blood vessels may form in excess to feed a cancer tumor. Once he finds the genes responsible for this vessel growth, he'll try to figure out how to turn them off, and thus starve and kill tumors. Of some 30,000 zebrafish genes (roughly the same number as humans), about one of every 200 is important for blood-vessel formation. To find the genes, Essner knocks down the expression of one gene at a time. Then, he watches the development of the embryo to see if or how the gene would have affected blood vessel formation. "We're really searching for that small subset of genes that are important for this process," said Essner. "By screening for these new genes, we hope to identify new candidates for anti-tumor agents." How might this lead to a cancer treatment in humans? Once an anti-tumor agent is discovered, researchers will test it on other model systems. The hope is that it makes its way to a clinical trial stage for humans, and works. A short stint in industryAn early event that sparked Essner's interest in biology came in third grade when a scientist came to class toting a microscope. He remembers looking through the lens and watching a sea urchin embryo cleave and divide. He studied biology as an undergraduate at the University of Iowa, and while in graduate school at the University of Minnesota, he started to use the zebrafish as a model. Next came a postdoctoral appointment at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif. After that, he and his spouse both landed research faculty appointments at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah. But it was in his next position as scientific director for Discovery Genomics Inc., a Minneapolis biotech company, where Essner started to see the applications of his research. "It was my experience in industry that led me to believe I could make an impact on human disease. That you can easily transition basic research into therapeutic products," he said. After five years in industry, Essner and his family moved to the place he grew up -- Iowa. Other research using the zebrafish modelEssner's spouse, Maura McGrail, associate scientist in genetics, development and cell biology, will be one of the first scientists to use the zebrafish facility. McGrail is developing a cancer model in zebrafish embryos, essentially creating a fish that gets cancer. Her long-term goals are to find chemicals that will inhibit tumor formation and growth. Often, cancer growth in zebrafish is quite similar to that in humans. In another collaboration with Essner, veterinary specialist Dusan Palic will look at how the immune system in the zebrafish responds to different stimuli, in turn, giving information about how the immune system functions. Essner is interested in this collaboration because cancers develop the ability to evade the immune system. "We have become fairly proficient at curing mice of cancer. However, when we go to the clinic with these same tools, they don't seem to work so well on humans," he said. "And so it's really asking for a different kind of approach. "Maybe screening more genes and understanding what those genes are doing will lead to more effective therapeutics." |

Quote"We have become fairly proficient at curing mice of cancer. However, when we go to the clinic with these same tools, they don't seem to work so well on humans. And so it's really asking for a different kind of approach." Jeffrey Essner |