Inside Iowa State

Inside ArchivesSubmit newsSend news for Inside to inside@iastate.edu, or call (515) 294-7065. See publication dates, deadlines. About InsideInside Iowa State, a newspaper for faculty and staff, is published by the Office of University Relations. |

October 21, 2005 An officer and a psychologistby Samantha Beres When an Eagle Grove man recently violated a no-contact order and holed up in his house, local authorities took measures. They evacuated nearby homes, turned off the man's utilities and called in negotiators.

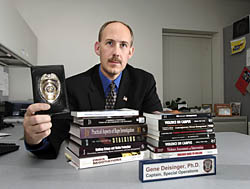

ISU Police officer Gene Deisinger specializes in threat management and crisis intervention. Photo by Bob Elbert. Sometimes jurisdictions within the state share resources like a top-notch negotiator. In this case, they called in one of the best: Gene Deisinger, commander of the Special Operations Unit of the ISU Police Department. While Deisinger doesn't spend everyday negotiating with a barricaded subject, threat management and crisis intervention are his specialties. He's the guy they often call in to talk a suicide victim down from a ledge or to crack a stalking case. In addition to his work in threat management, he oversees investigations, crime prevention, community outreach, internal affairs and public information for the ISU Police Division. His title says he's a cop but he's also a clinical psychologist, training that comes in handy on the job. "Law enforcement officers may not like to admit it," Deisinger said, "but most of what they do is psychology. It's dealing with human behavior. If you have a criminal investigation, the goals are different from what they are in the therapy room, but many of the approaches in terms of trying to draw people out to tell their stories are the same." From Wisconsin to IowaWhen Deisinger started college, he didn't intend to go into law enforcement, or psychology, though in grade school and high school, he remembers being a sounding board for friends who came to him for support and to ask questions. He went to the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point with interests in aerospace engineering and computer information systems. But when he took psychology 101, he was hooked. His professor, a sixties throwback, came to class wearing flowered shirts and sandals. "The man exuded this fascination with human behavior. It was contagious," Deisinger said. "I was just enthralled about how we learn, how we behave, how we're influenced." In 1987, he came to Iowa State to work on his doctorate in psychology, and two years later, he married Maureen, whom he'd met at Stevens Point. While working on his degree, he was hired in Student Counseling Services and ultimately promoted to assistant director. After there were a couple of suicide attempts on campus in 1994, CIRT (Critical Incident Response Team) was created with Deisinger as the point person for threat management. In 1998, he moved over to ISU Police full time, first as a civilian, then, after attending the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy, as a certified officer. Wearing many hatsWhat Deisinger likes about his job is the variety. Occasionally he'll don a uniform and work a home football game. This spring, he'll teach a seminar on threat management for the Honors Program. He gives guest lectures on workplace violence and related issues both on campus and for professional organizations. Off campus, he's the primary negotiator for the Ames Police Department and a member of the crisis negotiation team for the Story County Sheriff's Office. He also trains local, state and federal officers on a variety of police psychology topics, including dealing with the mentally ill, hostage negotiation and crisis intervention. "I emphasize that law enforcement has become the only 24/7 social service in nearly every community," he said. "Across the country, law enforcement agencies, particularly after regular business hours, are the first point of contact for people in crisis." Hence the need for well-trained officers who can recognize a mental illness or severe emotional distress so they can de-escalate a situation, he added. As a local representative for the Joint Terrorism Task Force, he works with the FBI to help prevent and deter acts of terrorism. Deisinger pointed out that working with other agencies has an added benefit -- he can draw upon their resources to help crack a case. Falsely reported casesDeisinger also does good old research. He and collaborators are studying how to better detect false reports of violent crimes. They will compare at least 100 false reports collected nationwide with reports of similar crimes that really did happen. "What are the motivations and what are the mechanisms of false reports?" Deisinger said. "I think psychology and human behavior are fascinating. I think psychologists need to be doing more to take what we've learned about human behavior out to the public." The goal in his research is to give law enforcement officers better tools to detect false reports more reliably. He'll also explore how the university policing environment might compare to other settings in regard to false reports. "I enjoy asking questions and finding answers to questions. That's what I do as a detective, it's what I do as a clinician. We're just doing it in a more structured way with the research," he said. Humanitarian aidDeisinger, the cop, the psychologist, the teacher and researcher also is a humanitarian. When the Red Cross asked if he'd go to Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina hit, he knew he would say yes. He and his wife had just been discussing how they could do more to help with the disaster relief efforts. He just had to figure out the logistics. The Deisingers have two sons, ages 4 and 6, and he's devoted to his family. "Maureen was a trooper in taking on the challenge of being a single parent during the time I was deployed," Deisinger said, expressing gratitude for the support of his family that made the trip possible. From Sept. 16 to 30, he worked in Houma and Gray, La., in charge of mental health services for both disaster victims and Red Cross workers. He said that the life-affirming experience gave him an appreciation for the land and a better understanding of the people. "I didn't quite see what was appealing about the bayou," Deisinger said. "But after having seen a small portion of it, even the hurricane affected areas, it is really a remarkably beautiful place." He also was impressed by the connection between the people and the land, something that he's only encountered in Iowa among some farming families. For people who grew up in the bayou, with families that have been there for generations, this strong connection is more the rule than the exception, he said. Deisinger called in to ISU several times so that friends and colleagues back home would have a link to the experience in the stricken area. Annette Hacker, director of news service, transcribed his notes and put them online. Deisinger's Katrina blog is at http://www.iastate.edu/~nscentral/news/2005/sep/katrina. One day in particular was extremely difficult. Deisinger told of a man who had lost everything, yet he felt blessed that he and his family survived. "One of the reasons I went to Louisiana, one of the reasons I work in a crisis-related job, one of the reasons that I like crisis intervention work as a therapist, is that I think it's a privilege and incredibly rewarding to be with people in their worst moments, and to help them find their way through it," Deisinger said. "I can't think of a much more precious gift another person offers to me, than trusting me enough to allow me to help them at a point when they need it the most." |

Quote"I can't think of a much more precious gift another person offers to me, than trusting me enough to allow me to help them at a point when they need it the most." Gene Deisinger |