|

|

|

|

|

|

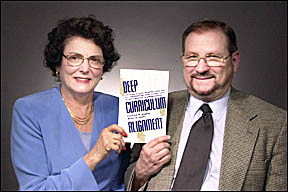

INSIDE IOWA STATE June 8, 2001 One nation, one curriculumby Kevin BrownYou can't test quality in. You build it in and test to see if it is there. Betty Steffy and Fenwick English, both professors of educational leadership and policy studies, believe this notion is the hope for education. The key to improving student education, they assert, is to develop a national curriculum and then test that core concepts are being learned. The husband and wife team, who do several school assessment studies each year around the country, published a book earlier this year on testing. Deep Curriculum Alignment -- Creating a Level Playing Field for All Children on High-Stakes Tests of Accountability focuses on the Texas educational system. It takes to task current standardized testing theories and the tests' impact on both student learning and esteem. They use Texas -- a state that ties funding to performance on standardized tests -- for their research and include urban, suburban and rural school districts in Houston, Austin, Dallas and other communities. The couple draws upon their professional experiences in reviewing current testing practices. Steffy served as deputy superintendent of instruction for the Kentucky Department of Education (1988-1991) during a major overhaul of that state's system. The new system now is considered a model for the rest of the country. English served as vice-chancellor for academic affairs at Indiana University, Purdue University, Fort Wayne (1996-1998). Both are former school principals and superintendents. "This book is as contemporary as you can get," English said. "It is a balanced view of the pros and cons of testing, particularly as used in Texas." An example in Texas On the pro side, they like Texas' emphasis on ensuring that minority achievement equals majority student achievement. That forces teachers and administrators to attend to at-risk learners. However, they are critical of the inconsistency in curriculums throughout Texas and, indeed, the country. The absence of consistent content in core learning is a major flaw of standardized testing, the couple agrees. For example, every state requires students to study state history, geography and other "local" topics, sometimes to the detriment of more universal education needs. "This is a peculiarity of the American approach to education," English said. "It is a function of local control of education. For example, should states require one year of, say, Mississippi history, in place of world geography? This is unique to America." Steffy and English point out that most other industrial countries -- including Germany, Japan and Finland -- have national curriculums and produce students who score consistently higher than American students in areas such as math, science and geography. A current political and parental theory is that a lack of testing is the reason for this general poorer performance by American students, the couple said. "Many people believe the way to achieve better schools is by testing more often," English said. "But, you don't get a better pig by weighing it more often. You achieve a better pig through a well-planned nurturing program. The same is true for education." "The new (federal) administration's approach to education seems to point in that same direction," Steffy said. "They seem to favor testing, testing and more testing until everyone gets it right. The reality is, you just can't test quality in." Separate funding and test performance A negative impact of using testing as one means to control education funding is that learning "fields" aren't always equal. Differences in things such as school district wealth, local cultures, home environments and parental involvement are ignored when all schools are judged under the same guidelines. This establishes a system in which poorer school districts continue to fall behind or concentrate so much on teaching "testable material" that educational value and understanding is lost to memorization. "Withholding funds to school systems that don't show test gains doesn't work because tests and curriculum are not directly matched," Steffy said. "The same is true for paying teachers according to student test scores. You might have the most committed teacher in a district working in a classroom where other learning variables -- access to materials, parental involvement, economic status -- carry more weight in lowering test scores than that teacher's ability to instruct. Such policies just reinforce the inequity." And at the other end of the spectrum, higher-performing classrooms or schools could be penalized for success on early tests, because it's much harder to make gains in the 90th-percentile level than in the 60th-percentile area, she said. "The bottom line is, you have to teach what you test and test what you teach," Steffy said. "Parents think tests teach what is important and they don't do that. Politicians and parents have a comfort level with testing because there is this supposed magic in numbers -- like testing can offer a quick fix. It is just a single measure of accountability." "If hard work alone could get all students to the same place," English said, "we'd be there by now." Both Steffy and English said a national curriculum would negate many of the weak points of standardized testing by providing a level educational learning field. "If all children are learning the same things, issues such as race, socioeconomic status and poverty cease to be significant to the argument," English said.

|

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2001, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |