Feb. 18, 2010

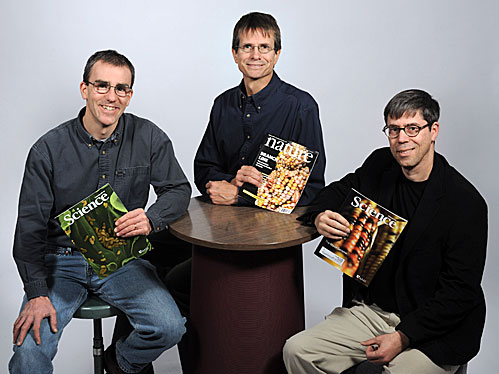

Plant science researchers (l-r) Adam Bogdanove, Erik Vollbrecht and Patrick Schnable. Photo by Bob Elbert.

The cover boys of plant science

by Meg Gordon, Plant Sciences Institute Communications

Erik Vollbrecht, Patrick Schnable and Adam Bogdanove have achieved cover boy status -- each capturing a cover story in Nature, Science and Science, respectively. Publishing work in either of these top peer-reviewed and widely read scientific journals is like winning a ski race on the World Cup circuit. Having your article selected as 'the' story of the issue is equivalent to winning Olympic gold.

"You could hope for one cover, could deserve five and get none," said Erik Vollbrecht, assistant professor of genetics, development and cell biology. Honors aside, such achievement is particularly advantageous because the popular press monitors these journals, creating avenues to share discoveries more broadly.

So, just who are these champions of plant science prose?

"A Simple Cipher Governs DNA Recognition by TAL Effectors" (in Science), Matthew J. Moscou and Adam J. Bogdanove

Bogdanove and Moscou deciphered the homing signals specific bacterial proteins use to find their DNA landing pads.

"The potential biotechnology applications are huge," Bogdanove said. Disease resistance, gene therapy and strategies for understanding how genes work, are but a few.

Adam Bogdanove

Virginia native, Eagle Scout, former gymnast and self-described tinkerer, Bogdanove ("Bog-DON-ov") studies the molecular equipment a particular bacterial pest uses to infect and multiply in rice. When this modest microbe (Xanthomonas oryzae) that causes bacterial blight or leaf streak spreads through rice fields, it can reduce harvest by up to 30 percent.

One of six siblings who chose fields as diverse as social worker and comic book artist, Bogdanove describes himself as "the lone geek in the family." Associate professor Bogdanove, who completed a doctoral degree in plant pathology at Cornell University in New York before joining Iowa State, was not interested in plants as a kid.

"I did collect bugs though," he said. "Once I caught a big bumble bee, put it in the kill jar and mounted it with a pin. I realized a bit later when it started to buzz there in the cigar box that I'd only anesthetized it."

The struggle and subsequent mercy killing of the bee, along with an undergraduate experience in a neuropsychology lab involving rat brains at Yale University, may have influenced Bogdanove's eventual preference for flora over fauna.

Bogdanove's winning discovery, featured on the cover of the Dec. 11, 2009, issue of Science spells out how special molecules (in this case proteins) from the bacterium's equipment bag schuss into the nucleus of the rice plant cell and plant poles on tiny and precise pieces of DNA. There, the proteins set off more molecular events that culminate in a rice plant 'yard sale' -- with the microbe besting the plant's natural defenses.

"Architecture of floral branch systems in maize and related grasses" (in Nature), Erik Vollbrecht, Patricia S. Springer, Lindee Goh, Edward S. Buckler and Robert Martienssen

Vollbrecht's article about corn kernels and the genetic controls that set them in neat rows along the ear earned the cover because the work tied together several fields and began to answer a long-standing hot question in corn biology -- something farmers had been observing for centuries.

"The maize ear is a botanical freak," Vollbrecht said. "It is so productive and there is nothing else like it in the botanical kingdom."

Erik Vollbrecht

Avid back country skier Vollbrecht grew up in the San Francisco Bay area. Though always interested in the natural world, Vollbrecht preferred mathematics and later, physics. After completing an undergraduate degree in biophysics at the University of California, Berkeley, he fortuitously began a job as a laboratory technician in a corn genetics laboratory on campus. He fell in love with genetics, and as the technician who did all the work, earned his first Nature cover story -- the discovery of the first master developmental control switch gene found in plants (March 21, 1991).

"What I love about genetics is it's all about patterns," said Vollbrecht, who revels in taking things apart -- cars, appliances and now computers. "That's a part of what being in the lab is about, figuring out how to make things work. And the great thing about corn genetics is you get to do half of your work outside."

Inspired, Vollbrecht went on to earn his doctorate at Berkeley, mixing his studies in genetics with old school plant biology/plant development. "Genetics is a tool and tools are great, but you have to know about what you're working on," he said.

Before joining Iowa State in 2003, Vollbrecht worked as a post-doctoral researcher at the 120-year-old non-profit research campus of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSH) in New York. CSH is rich with history and is the scientific home to James Watson, who along with Francis Crick, won the Nobel Prize for discovering the helical structure of DNA. There he began laying the scientific foundation for his second and most recent Nature cover article -- the Aug. 25, 2005, issue.

"My work is really about understanding natural and domesticated species, and the differences between them," Vollbrecht said. And it absolutely depends on access and the ability to compare domesticated species with their ancient wild relatives, championing preservation of native habitats.

"The B73 Maize Genome: Complexity, Diversity and Dynamics" (in Science), Patrick S. Schnable, et al.

"Maize or corn is a crop of the Americas -- it's huge in the U.S. and the world. It is also a wonderful biological model," Schnable said.

Patrick Schnable

Vollbrecht's field also relies on DNA sequences like that generated for the maize genome by the group led by Baker professor of agronomy Schnable. Schnable secured the Nov. 20, 2009, cover of Science by leading a coordination effort culminating in the maize genome sequence, plus reports by people who made use of the sequence to further their understanding in their own areas of science. It was an ensemble -- not just the sequence, but the demonstration of its usefulness.

Schnable grew up in upstate New York after spending his earliest years in Sun Spot, N.M., where his optical engineer father worked on lens design at the National Solar Observatory. Schnable, too, was a Boy Scout, hiking and camping in the Adirondack Mountains, picking blueberries "above the treeline, where the whole world opens up."

He readily admits he is not one who relishes taking equipment apart or putting it together. But "I did some truly amazing stuff in college to keep my car running," he recalled.

As an undergraduate at Cornell University, New York, Schnable was required to complete a communications course. It included writing, debate and oral presentation.

"I hated it," he said. "But looking back, I'm really glad I took that class. It helped me overcome the typical fear of public speaking." He has become one of the most skilled science communicators in his field.

An avid reader of science fiction as a kid with an affinity for math and science, Schnable liked plants, adding to his parents' gardens at every opportunity. From an early age, he wanted to be a plant breeder, but after earning his undergraduate degree in agronomy, he discovered that he really wanted to understand the "why," the underlying biology of plant breeding.

Schnable completed his doctoral degree at Iowa State in plant breeding and cytogenetics. Following post-doctoral study at the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding in Germany, he joined the Iowa State faculty, where he is a leader in the maize genetics community.