|

|

|

INSIDE IOWA STATE January 18, 2002 Pursuing a cure for Parkinson's disease

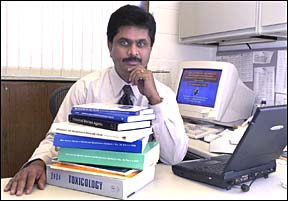

He shuffles to the kitchen table and takes a seat. "Shakes" plague the man, a retired farmer. Now, he sits on the wooden kitchen chair, hands folded and feet crossed to prevent the tremors. Lately, they aren't so bad because of the medication. Sinnement and Mirapex help ease the muscle spasms in his frail, 80-year-old body. Archie Berends misses farming; it has been his whole life. A month ago, Joyce Kruse's family noticed she wasn't her old optimistic self. Joy Meyer, Kruse's daughter, said that once Kruse realized her condition would require her to stay in a nursing home indefinitely, she became depressed. Tremors affect Kruse's ability to feed herself, the right side of her face has become a "mask" of sagging muscles and walking is an obstacle. Farm link Kruse and Berends have several things in common. They both grew up on farms. They both have been around common farm chemicals, including pesticides. They both have Parkinson's disease, a disease that attacks the portion of the brain that controls movement. The director of the Parkinson Disorders Research Program at Iowa State, Anumantha Kanthasamy ("Con-ta-SAW-me"), says there's overwhelming epidemiological evidence to support the link between Parkinson's and exposure to farm pesticides. Already, he has written approximately 50 papers and books about Parkinson's. He's out to make the evidence indisputable. Kanthasamy has received a $314,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health to determine the role that certain environmental factors play in the cause and progression of the disease. Kanthasamy said there is hope for Parkinson's sufferers, and Berends and Kruse are just the type of sufferers he desperately is trying to help. His 10 years of experience working with the degenerative disease began with his grandfather's affliction with the disease in Siruvalur, India. When Kanthasamy left his homeland in 1989, he already had received a B.S. in chemistry, M.S. in biochemistry and Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Madras. He studied the effects of chemicals on nerves and dopamine cells the cells that control movement and degenerate during Parkinson's during postdoctoral training at Purdue University. "My undergraduate work was in chemistry and I was interested in how chemicals influence biological effects," Kanthasamy said. After five years of clinical experience with the disease at the University of California, Irvine, Kanthasamy decided to pursue the agricultural link to Parkinson's disease and came to Iowa State. "One of the problems is the progressively degenerating condition," said Kanthasamy, associate professor of biomedical sciences. "Current treatment doesn't intervene with the progression process, it only provides temporary relief. This research could lead to a cure." Parkinson's is especially prevalent in people exposed to pesticides and other toxic chemicals, Kanthasamy said. Farmers are at the top of the high-risk list. Normal onset of Parkinson's occurs around age 55 and nearly 1 million Americans are affected, with an annual societal cost of $5.6 billion, according to Kanthasamy. Searching for a cure There are several biological and molecular aspects to the disease, he said, which makes finding a cure a difficult task. Recently, in his labs at the Veterinary Medicine college, he discovered that blocking the protein caspase stops degeneration of dopamine cells in the brain, which could mean a stop to the progression of Parkinson's. Dopamine is a chemical compound found in the brain that transmits nerve impulses and is involved in the formation of the hormone adrenaline. These cells die as Parkinson's progresses. Now he is looking for the mechanism that chemicals use to kill dopamine cells. In his experiments, Kanthasamy looks at effects of chemicals on cell cultures and how cells die over time. Chemicals currently under Kanthasamy's scrutiny include Dieldrin, a now-banned pesticide used heavily in farming operations 15 to 20 years ago. Dieldrin is in the same class of chemicals as the once ubiquitous pesticide, DDT. Kanthasamy also is looking at MMT, a compound commonly used as a gasoline additive, and rotenone, a herbicide heavily used today in farming and inside the home, usually as rodent control. Protection as prevention Kanthasamy said minimizing exposure to these and other chemicals is important. Wearing protective clothing is key. Chemicals weren't as feared when Berends began farming as they are now. Growing up on a farm in northern Iowa, he helped with the beans, corn, cattle, hogs and chickens. "We used to use rotenone in the chicken houses," Berends said in a muted voice. Kruse grew up on a farm in northwest Iowa. She knows chemicals were used on their farm, and she has heard of the pesticide rotenone. "Oh, father would be very careless with it," she said. "It would get over things; he wouldn't wear gloves." The link between Parkinson's disease and farm pesticides soon will be understood, Kanthasamy said. Proving that farm pesticides and gasoline additives could have a hand in the onset of Parkinson's could change the way the agricultural world does business. It could change medicine. "It could provide a cure," Kanthasamy said. |

|

Ames, Iowa 50011, (515) 294-4111 Published by: University Relations, online@iastate.edu Copyright © 1995-2001, Iowa State University. All rights reserved. |